Since the beginning of a full-scale war, the Ukrainian film industry has been going through hard times. After several years of active development, almost all production processes had to be put on hold, and many cinematographers joined the Armed Forces. One of them is the chairman of ForeFilms Volodymyr Yatsenko. And although most of his time is taken up by the war today, the film producer has not abandoned his profession either. His production company has several projects in work that will reach Ukrainian viewers sooner or later, and Yatsenko himself continues to participate in industry events. For example, he did not miss the recent Cannes film market, where Ukrainian content was presented to an unprecedented extent. Sometimes he conducts negotiations with partners directly from the trenches. Moreover, in between the front and production duties, Volodymyr managed to find time for an interview. And we took advantage of this by asking the cinematographer about the present and future not only of his production company but also of the entire Ukrainian film industry.

– Volodymyr, what are your impressions of your recent trip to the Cannes Film Market? Many people now say that Ukrainian content is in great demand worldwide – is it really so?

– Volodymyr, what are your impressions of your recent trip to the Cannes Film Market? Many people now say that Ukrainian content is in great demand worldwide – is it really so?

Yes, because there are objective prerequisites for this. For example, previously when a Ukrainian film was included in the program of one of the big three film festivals – we are talking about Cannes, Venice, and Berlinale – it was something incredible. And today that is the norm, and people's reaction is more like: "Why only one?". Of course, you get used to good things quickly. But one must take into account the objective reality: for example, in the official selection of Venice, an average of about 40 films are presented annually – 20 each in the main competition and the "Horizon" program, another 40 – in Cannes, almost 80 – in Berlin, where there are many competitions and other systems. Let's talk about two hundred films selected for these festivals and more than 30,000 films released every year. That is, you can mathematically calculate the chances. Roughly speaking, most producers, despite a super successful career, never attend the big three European film festivals. Recently, Ukrainians have been going there regularly – for example, we will have our third Venice this year. I think this shows that not only are we good guys but also that Ukrainian content is popular. It is certain that in 2022 interest in Ukrainian content will be specified in connection with the war. It has its pros and cons: on the one hand, many films that have nothing to do with the war do not get as broad coverage as they would otherwise, but on the other hand, movies related to the war get additional media coverage. This can also be traced in Cannes: the rather strong original, but at the same time, not related to the war, the film Pamfir made it only to the fortnight – this is good, but it is an unofficial selection, and the film Butterfly Vision which tells about the war, made it to the official selection section Un Certain Regard.

– Are the requests related only to the war?

– Mostly yes. For example, we now have a lot of requests for screenings, especially charity screenings, of Valentyn Vasyanovych's films. We even told him about this: "Hey, mate, why did you choose 2025 as the year when the war ends? You could have shown some mercy and made it 2023 at least!" (about the Atlantis movie. – MBR). But seriously, I think this is a topic of great discussion within the industry that is yet to come. I can't speak for everyone, but I personally would absolutely not like to create a projection of a victim nation in a movie. This is what our colleagues from the former Yugoslavia do – they still make movies about the war. Twenty years have passed, but when it comes to post-Yugoslav cinematography, everyone understands that it is either about the war or related to war trauma. I would not like that to happen to us. There will be war movies, but I will try to avoid them.

In general, even before the war, we had a lot of films about our, let's say, negative specificity: we have a bad ecological situation, a strange relationship with the government, etc. And I would like that in a few years, in the movie industry, we could compete not only in the field of our unusualness (which, of course, in general, is not bad) but also in how ordinary we are. So, for example, a Ukrainian comedy could take the place of Another Round. Just imagine: we in Ukraine are shooting a comedy about three drinking high school teachers. I'm sure it would be ten times more fun than the original: the percentage of alcohol would be higher, and the heroes' actions would be more entertaining. That is, there is nothing holding us back except mental blinders. Of course, we should not forget that no one is waiting for us with open arms – no one is giving us their place, money, and rent. Therefore, we have to fight for our place, but this is good and right. In general, I am in favor of us becoming leaders in the system of the new normality in Europe. This is a cool challenge, and nothing prevents us from setting such goals.

– ForeFilms already has a project like that – the non-war comedy Luxembourg, Luxembourg, which you presented at the Cannes Film Market. I will also ask about it, but first, tell me why it was important for you to go to Cannes in person. Considering your service in the Armed Forces, it was undoubtedly associated with certain difficulties.

– There were many reasons, everything coincided, so I could go there. On the one hand, there are several films, including Luxembourg, Luxembourg. I will make a statement regarding the international festival a little later (now we are waiting for the press conference and confirmation), but in general, we have found one of the best and most interesting sales companies in the world – Celluloid Dreams. If you go to their website, you will see that even the header says "the directors label", which means that they take care of directors. At one time, they discovered François Ozon, and worked with many other authors – they have very good taste. And Hengameh Panahi, the Iranian owner of the company, is generally considered a legendary person in her realm. She was one of those who built the sales business, and it is a great honor for us to work with her. Hengameh takes films very seriously: after watching the editing of Luxembourg, Luxembourg, she wrote us a huge letter, although salespeople usually don't do this. She is not afraid to work with difficult, complex projects. For example, The Painted Bird is their title, they work with Takeshi Kitano and Noah Baumbach. They have many names, and the company is trying to grow with them.

– So is there a chance that Luxembourg, Luxembourg isn't the last film by Antonio Lukich the company has picked up?

– I would like to believe so, of course. But they did not just give us ground, but also help a lot. We own the rights to the film, which is completely unbelievable, they do not take their commission, only cover the costs, and they also say: "We will sell your film, but we will do it for you so that you can earn something, and help Armed Forces of Ukraine." This is extremely important because none of the things that used to bring in money (in my case, advertising) are working now.

– And how did the agreement become possible, and who initiated it?

– This is an interesting story. I know almost all prominent salespeople – European and some global. After watching Xavier Legrand's incredible film Custody (Jusqu'à la Garde), I learned that his distribution company is Celluloid Dreams. I've been dreaming of working with them ever since. When Vasyanovich and I were making Reflection, I wrote to all possible salespeople, including them; however, without much hope. They suddenly got involved and sent an emotional letter with inhuman praise to Valentin. But it so happened that by that time, we had already made a deal with another company, New Europe. I was honest about it, and then something happened that really surprised me: Celluloid Dreams wrote another long letter to us, and the same to New Europe, saying something like: "Dear colleagues, you have an incredible gem in your hands, we are very pleased that you are in charge, and we believe that you will be able to polish it." That is, they were sad but understood and accepted our decision to work with New Europe. And when we finished editing Lukich's film, Celluloid Dreams was one of the first companies I wrote to. They took a look, and confirmed their interest; after that, I didn't write to anyone else. The stated conditions are their initiative; they said that they want to help us this way. Although we tried to offer other options so that they could also earn something. What struck me was the incredible delicacy with which Celluloid Dreams treated the film, and their vision in many ways coincides with my own.

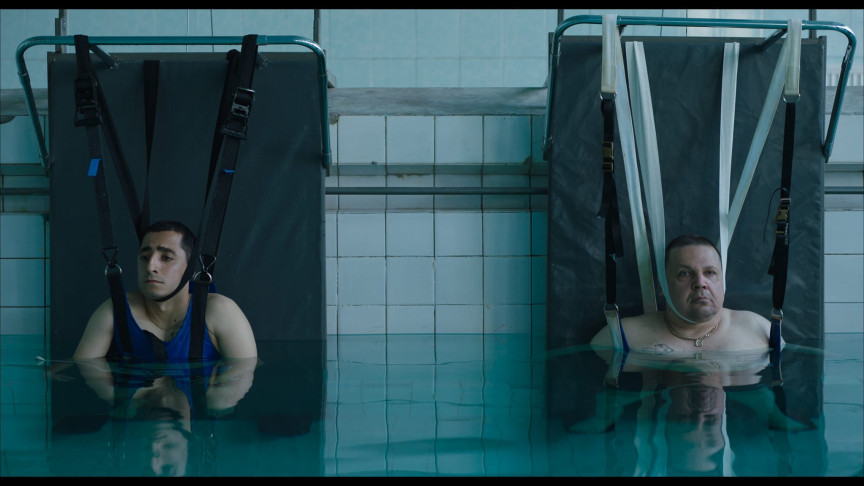

– You probably presented Pavel Ostrikov's film You Are the Universe to potential partners in Cannes. Were there any agreements regarding it, and at what stage is the film now?

– The last filming block was supposed to begin on February 24 – four days with the French star. We made an agreement with the actress Audrey Dana, we had already held rehearsals, and she was supposed to fly to Ukraine that day. But a week before the start, her representatives felt something and asked to postpone the start of filming to March 1. And as you understand, that was no time for filming. Currently, we are looking for partners with whom the film could still be completed. It is significant for us, that almost 85-90% of the material was shot, and the most difficult part was with the huge scenery, parts of which were also moving. Apparently, no one has done this before in Ukrainian cinematography, and I was very eager to create a Ukrainian sci-fi that we could be proud of. We have an incredible lead actor, Vova Kravchuk, whom we have been looking for for a year and a half and who is now also in the Armed Forces of Ukraine. This scares our colleagues: one of the two producers in the Armed Forces, an actor in the Armed Forces, so the risks are very high. There were many talks about this project, but no agreements – people don't believe that it can be carried out. Although they didn't believe it before either. We promoted the film for three or four years, and everyone doubted that it was possible to create it for such a small amount of money. Our task is to prove the opposite, so in this case, I was in no hurry. We already have a sales company – Best Friend Forever (they worked with Vasyanovich's film Atlantis). Now we are negotiating with several European companies that would act as co-producers and help complete the shooting this fall.

– I guess these may be French companies.

– On the contrary, we do not negotiate with French companies because we would have to give them the entire French market. And in this case, the French market will be huge, as the story is tied to the country, and the actress is French. We are now talking with Italians and Irish, but I can't tell you the details at the moment. Another project that I presented on the film market is Felix and Me by Iryna Tsilyk. Its premiere will take place this year at one of the international festivals (which one I can't tell yet). In Cannes, we were looking for sales companies and held several negotiations. In general, we did a lot of work there but I also had some personal motives – I really wanted to be with my wife Anya, who is my part-time partner-producer. We don't see each other at home, since I'm in the Armed Forces, and she's due to give birth in September, so Cannes was a way to spend at least a little time together.

– How did the start of the full-scale war, in general, affect the work of your production: how many projects were in active work on February 24, and how many of them stopped?

– It affected the company a lot. First of all, the mentioned films Luxembourg, Luxembourg and You Are the Universe. The first one was almost ready; the second one still needed some shooting and a lot of post-production work. In addition, we were supposed to start filming two projects that won the pitching before the war. One of them is a very cool Israeli-Ukrainian story Home, the debut feature of Israeli director Or Sinai, which won the Production Award from TorinoFilmLab (40,000 euros). Now the project is on hold till "after the war." The second story is Nariman Aliyev's film Ortalan, which won the Ukrainian State Film Agency pitching and was also selected for the Berlinale Co-Production Market. We planned its filming for the spring-summer of this year, but now we don't know when and if it will take place. We also had several projects in development: a new film by Lukich, a new film by Vasyanovich, and a feature directorial debut of my wife Anna Yatsenko (Sobolevska). Plus, we were developing a new Ostrikov project. But now everything is halted. There is no development, no money for development, neither Ukrainian State Film Agency nor Ukrainian Cultural Foundation have any money. I think that the film industry in general has been dealt a devastating blow, and I do not expect any miracles at all in the next two years – according to the most optimistic forecasts. Yes, those who left (both women and men who managed to escape) can theoretically build a career somewhere in Europe, maybe it would even be right for them, but domestically the industry is in a very difficult situation.

– At the same time, as I understand, the post-production of the film You are the Universe is still underway.

– Yes, I came to this meeting from an editing session. We are currently putting it together, but three scenes are missing, two of which we want to shoot in the fall and the third – later whenever we have an opportunity.

– Do you have an idea of how much the war will slow down the post-production stage? Before the invasion, you were cautiously planning a 2023 premiere.

– Yes, we thought we would be in Cannes in 2023, but now I don't know what the deadlines will be. We are still trying to make it, but I don't really believe it will work out. Although this is a very Cannes film, it is both an authorial and, at the same time, an audience one. This is a new thing for us, which is called art mainstream. I love this kind of movie – we wanted to make movies like this before the full-scale war started. We had everything planned for three years ahead, and now nothing is clear at all. On the other hand, this is also a kind of new step that we are taking. Therefore, we inextricably link our lives with Ukraine, we are not going anywhere.

– And what about the movie Luxembourg, Luxembourg?

– It is also in the post-production stage, and now only the editing is ready. Work on sound, color correction, and music is being carried out in parallel. The latter is especially difficult now: it has become difficult to buy music because before the war Ukrainians contacted most of the companies that own the rights through Russian hubs. Currently, we do not do this in principle, and new contacts cannot be established in a day.

– To what extent did the war affect the budgets of these films?

– Of course, everything became more expensive. I can't tell you the exact numbers yet, but I understand very well that when the time comes to finish the shooting of You are the Universe, we will need to complete the scenery, and the price tag will be significantly higher than before February 24. And this is just one example out of many. Fortunately, most of our contractors have not recalculated their rates yet, but how long that will last I cannot say. In the end, I think everyone is in trouble: everything is going up in price, and everyone will lose money. I don't know what the Ukrainian State Film Agency will do about it, but a lot of people will never be able to finish the films they have started for objective reasons. And we need to start thinking about how to deal with them now.

– In Cannes, you met with fellow producers and representatives of the Ukrainian State Film Agency – perhaps such conversations are already taking place?

– As far as I know, no. There is a lot of uncertainty now: many people left, some joined the Armed Forces, and the industry was actually put on ice. By the way, many actors joined the Armed Forces – I've met a lot of them, as well as screenwriters (for example, Maksym Kurochkin, who was wounded), but there are almost no directors and producers. Perhaps they are not ready to defend and die, because they are people of, let's say, intellectual work...

– As I recall, you were quite serious about the possible invasion of Russia before and carefully planned only two Ukrainian premieres for 2022 – Felix and Me by Iryna Tsilyk and Reflection by Valentin Vasyanovych. How about those plans now?

– We don't have any plans now; we have postponed everything. Yes, I have heard from many that it is necessary to have fun despite the war, but it does not seem right to me. I understand the concept that we are fighting here so that others can live peacefully, and I have no problem with that. But still, I would like to have a thoughtful dialogue with the audience, and the part of the audience who are currently fighting and cannot go to the cinema is especially valuable to me. So we postponed all premieres indefinitely.

– Is this more of a moral than a business issue for you? Do you mean that for you it is less about the closed cinemas and more about the fact that entertainment is not at the time?

– For me, morals and business are related things, but yes, now the thing is that this is not the right time. In addition, the authorial cinematography (which I work with) in Ukraine is not a business, unlike in Poland, for example. What kind of business could it be when before the war in Ukraine, TV movies with exclusive screening rights were bought for $10,000–20,000, while in Poland the price is $150–200,000? I'm not talking about Germany, where it can be $400,000 or more. Cinema distribution is nothing to speak of too. The only way to make money from authorial cinema is to have a cinematheque of 30-40 titles. We were saved by the advertising production, which worked, but today we only have scraps left. What will happen next is very difficult to say, but I think that the author's film, and cinema in general in Ukraine, will not be a business for a very long time. Even if we assume that when we win, there will be a huge investment in culture, it seems to me that it will most likely be drowned in the clatter of pseudo-patriotic films. Of course, I wouldn't like it very much, but to avoid it, we need a thorough discussion within the industry: what should we do during and after? And we are not discussing it.

– In the end, I'd like to ask something besides the movies. In March, you and Sergey Mikhalchuk started the Ukrainian Witness project about the war. Tell us more about this initiative.

– That is elementary. We got together in such a powerful group – me, Mykhalchuk, Yuri Gruzinov, and two other guys not from the industry – and thought about what we could do. And since we know how to film, we started filming everything we see: Irpin, Bucha, evacuations, the work of the State Emergency Service, etc. We did this as long as we could, and then the Russians began to target people with the "Press" badges, and when we arrived at the positions, our military turned us back. So we organically understood that to continue filming, we need to join the Armed Forces (laughs). After a small casting of units, we chose ours, all five voluntarily mobilized, and now we are soldiers with the option to film. Our initiative was never exactly a project in the usual sense: we simply filmed and posted everything we saw. From the very beginning, our materials were copyright-free, and the video about Irpin was probably the most popular – we were one of the first to enter together with Defence Intelligence of the Ministry of Defence of Ukraine. It was a video without words: a beautiful spring day, birds singing, dogs running, and bodies lying on the roads. It was shown by CNN, and according to their statistics, 167 million people watched the video in the United States and another 35 million in the rest of the world. We also worked with the Ukrainian Volunteer Corps and were in the fields with rocket men. In brief, we were creating content and fighting at the same time. And now we continue to do it, but for obvious reasons, we do not show many things.

– Have you already figured out what you will do with the accumulated material?

– Honestly, no. At the moment, we are just filming, without specific goals. It began as witnessing not to lose one's mind and continues as a recording of oneself and the people around in new circumstances. It is very interesting, because war is a universal melting pot that creates this mass, and being inside the process is a priceless experience. Of course, there is a risk that some of us will be killed or all of us will be killed, but we feel that this is exactly what we want and must do.

– Even before mobilization, you had accreditations from the Ministry of Defense – how difficult was it to get it?

– It was not difficult for us since we were one of the first. Then, as I know, it became more difficult. A million pseudo-journalists appeared – all filmmakers became journalists. But the main reason is that journalists became priority targets for the Russians. So the Ministry of Defense rightly decided to limit the issuance of accreditations. Many from the industry started working as fixers, although they had no such experience before. And they were also killed, like, for example, our former colleague Sasha Kuvshinova, who worked for Fox News and died in Gorenka from the shelling of "Grad".

– How did you decide to mobilize in general?

– It was a hard decision. I had a long and difficult conversation with my wife. I have two soon-to-be three children. But that is exactly why I made this decision: I will have to explain to my soon-to-be-born son where I was and what I did during the war. Besides, it seems to me that the survivor complex is even more destructive than being in the trenches. It's like "Maidan" – on the front, we feel calmer than in the rear – there is an understanding that you are in the right place and doing the right thing.

– And at the same time, you continue producing...

– Yes. This is a very strange feeling: two very different worlds that do not intersect at all. It helps to distract. I think that war will last for a long time, so we have to learn to live in new conditions, in a new reality. In a positive sense, everything will definitely not end this year, and maybe not the next year either. Now you need to build your life differently. Well, at least try.