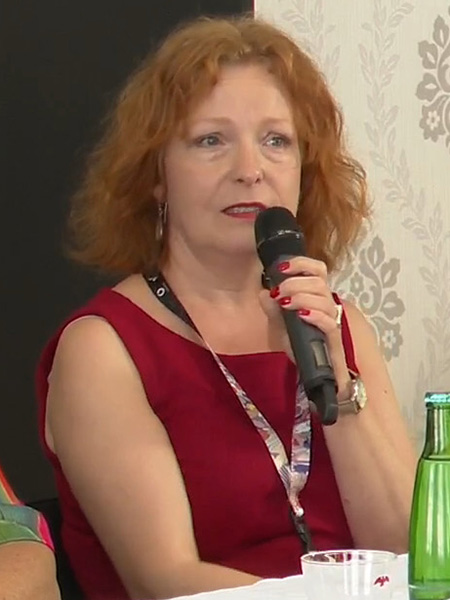

"Pavlina, there are a lot of applications to film commission from Russian filmmakers to shoot in the Czech Republic or for services, how do you deal with these now?" – "Not anymore." Such was the laconic and unequivocal answer of the head of the Czech Film Commission and the president of the European Film Commission Network (EUFCN) Pavlina Zipkova, during the discussion on "The impact of the war in Ukraine on the international film industry". Unfortunately, it was almost the only clear answer to the acute questions that were raised during the discussion that took place at the International Film Festival in Karlovy Vary.

But the lack of answers is not the fault of the speakers – representatives of the Ukrainian, Czech, Latvian and German industries. After all, these questions concerning the possibilities of financing Ukrainian films with European funds mainly lie in the plane of regulatory policy at the state and interstate levels. And among the many similar panels that have taken place within various industry events since the beginning of the full-scale war, the discussion in Karlovy Vary stood out precisely because it mainly focused on the strategic, rather than tactical, aspects of European assistance to Ukrainian filmmakers. That is why we summarized its main theses and proposals for you.

Pavlina Zipkova, mentioned above, spoke first.

Speaking about the actual topic of the discussion – the impact of the war on the international industry – she said that immediately after the beginning of the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine, the Czech Film Commission began to receive many questions from foreign partners (especially from the USA) regarding the safety of filming in Central Europe. "There were tens of questions every day, – Zipkova recalls. – So we produced this one-page material saying that Central Europe is a safe place to film, that we are surrounded by NATO countries. We decided not to put the information on Social media, we just silently put it on our website and informed the producers that it is there, that they can download it, and share it among their colleagues in case they are coming over here. Two days after that we were hacked – the virus came from Russia. By now we've already got the site up, but it was completely destroyed."

Speaking about the actual topic of the discussion – the impact of the war on the international industry – she said that immediately after the beginning of the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine, the Czech Film Commission began to receive many questions from foreign partners (especially from the USA) regarding the safety of filming in Central Europe. "There were tens of questions every day, – Zipkova recalls. – So we produced this one-page material saying that Central Europe is a safe place to film, that we are surrounded by NATO countries. We decided not to put the information on Social media, we just silently put it on our website and informed the producers that it is there, that they can download it, and share it among their colleagues in case they are coming over here. Two days after that we were hacked – the virus came from Russia. By now we've already got the site up, but it was completely destroyed."

However, such assaults did not diminish the desire of Europeans to support Ukrainian colleagues. In particular, Zipkova said that the EUFCN headed by her is preparing a special training program for representatives of Ukrainian film commissions, the purpose of which is to help them attract film crews and investments from abroad. "The purpose of film commissions worldwide is to attract inward investment to boost the local economy. And now this issue is even more important than before. Obviously, you might think ‘What is there to attract?’ – but one of the most sought locations in the world now are brownfields. As soon as the war is over, I believe, with our support, it would be a great place to film themes like that," Pavlina summed up.

Producer Dagmar Sedlackova, a representative of the Czech production company Masterfilm, a co-production partner of Maksym Nakonechny's film Butterfly Vision, focused on practical issues "here and now". In particular, how the Czech industry can help Ukrainian films in the final stages of production. Dagmar mentioned the Czech Film Fund with an annual budget of 1.6 million euros for minority co-productions. "We have two calls per year for minority co-production. Usually, there is one call in the spring and one in autumn. And Czech producers can apply even for the postproduction money," – she noted (the next competition should be announced already in July – details can be found here).

Producer Dagmar Sedlackova, a representative of the Czech production company Masterfilm, a co-production partner of Maksym Nakonechny's film Butterfly Vision, focused on practical issues "here and now". In particular, how the Czech industry can help Ukrainian films in the final stages of production. Dagmar mentioned the Czech Film Fund with an annual budget of 1.6 million euros for minority co-productions. "We have two calls per year for minority co-production. Usually, there is one call in the spring and one in autumn. And Czech producers can apply even for the postproduction money," – she noted (the next competition should be announced already in July – details can be found here).

When asked where a Ukrainian producer can find a Czech producer, Sedlachkova also had an answer. First, she recommended consulting the head of the Czech Film Center, Marketa Santrochova (her contacts can also be found at the link above), who "can help you find a good fit for your project." Secondly, she encouraged Ukrainian producers to subscribe to the page of the Girls In Film Prague organization on Instagram. The main mission of this community is to help filmmakers get in touch: both within the Czech Republic and in the context of international cooperation. "Even if you are not a female filmmaker," Dagmar added with a laugh, just in case, given the name of the organization.

Sedlachkova also mentioned the work of the online platform Creative Shelter, which is currently helping Ukrainian representatives of the creative industries who were forced to leave the country to find work abroad.

The next speaker was Latvian Uldis Cekulis (VFS Films), the first producer from a neighboring country to start a co-production project with Ukraine after the start of the full-scale war.

The next speaker was Latvian Uldis Cekulis (VFS Films), the first producer from a neighboring country to start a co-production project with Ukraine after the start of the full-scale war.

The project Сompany of Steel directed by Yuliia Hontaruk is a triptych documentary film about veteran volunteers, who returned to civilian life after being demobilized from the war in Eastern Ukraine in 2015-2017 but are forced to go to war in 2022.

Uldis, who has previously worked with Ukrainian projects (in particular, with Roman Bondarchuk's film Ukrainian Sheriffs), said that he first learned about the 2019 Company of Steel at B2B DOC. After the full-scale invasion began, he immediately contacted Yuliia and Ihor Savychenko (the producer of the film), asking how could he help. "There was a minority call by the Latvian Film Center in early march. So we admitted two projects, – he recalls. – Our film center asked for proof from the local organization that the money is given. Even the war is there. And your film center got the letter the second month. I also got a lot of support from Latvian filmmakers who were ready to drop everything to join in and help. Everything was very fast on both sides – it's just amazing!"

Shot from the film Company of Steel

The next speaker of the discussion Ihor Savychenko noted: "War is an unnatural thing. And the way we all act now is unnatural. Yes, as arthouse producers we know how to 'sneak', but..."

First of all, he talked about the project One Day in Ukraine (previously Day of the Ukrainian Volunteer) – a documentary film by Volodymyr Tykhyi, the first full-length project of the Babylon'13 association, created during the full-scale war. The filming lasted only one day, March 14, when Ukraine celebrates Volunteer Day (in general, the production lasted two months).

First of all, he talked about the project One Day in Ukraine (previously Day of the Ukrainian Volunteer) – a documentary film by Volodymyr Tykhyi, the first full-length project of the Babylon'13 association, created during the full-scale war. The filming lasted only one day, March 14, when Ukraine celebrates Volunteer Day (in general, the production lasted two months).

The producer noted the contribution of European colleagues to the creation of this project, recalling that most of the equipment was provided by the Czech Association of Producers, and Polish colleagues helped with post-production. Last month, the film was presented at the prestigious documentary film festival Sheffield Doc/Fest, where it won a special jury award. "We got several really nice contracts in Sheffield. And this autumn the audience of more than five hundred million people will watch the film, which is really good not just for us but for all Ukrainians because they will see the unreality of the war in Ukraine," Savychenko emphasized. And later, explaining this unreality to the Europeans, he added: "For those who do not understand the situation, I will explain. The protagonist of the film One Day in Ukraine, which we showed at Sheffield DocFest, was killed. It was Roman Ratushny. He was almost 25 years old. Roman was an activist from Kyiv. He was killed in action."

The unrealness of the war: tanks at the playground. Shot from the film One Day in Ukraine

Then Savychenko returned the discussion to global issues, noting that "the number one problem with Ukrainian films at the moment is the so-called country of origin, a very specific bureaucratic thing that stresses us the most in the entire European regulatory system." The fact is that to apply for foreign funds as a Ukrainian project, it is necessary to prove that there is financing from Ukraine, and this is currently impossible. What can be the way out? Savychenko suggests the following: "The idea is not about producers, but about filmmakers – screenwriters and directors can apply with a local producer in any country. If a Ukrainian producer has a project, it is not a very good idea to apply, for example, in the Czech Republic, but a good idea is to find a Czech partner, and if the director of the film will be considered a Czech director, it will be not a minority co-production in such case, but a majority co-production. The idea is to make the director choose the country of origin (currently, this status of the film is mostly determined by the producer and production. – editor's note). We need to detach directors from producers because this will be much faster and easier. It is very easy to make this small law to allow Ukrainian directors for at least three years to apply in any country and to be considered local directors. We are trying to push film funds of different countries to come to the European Commission for a media program with some kind of united proposal in this regard. But they say: 'Ok, the idea is good, but first of all you should be supported by local film funds.' And for example, in Germany alone, how many are there – sixteen, I think? The situation is very difficult at the moment."

The topic of Germany was continued by producer Simone Baumann, managing director of German Films, who has worked for many years with projects from Eastern Europe, in particular from Ukraine and Russia.

Baumann stressed that cooperation with Russia has become impossible since the events of 2014, and the current situation "is absolutely unacceptable." "Today there is no point to talk about Russia or cooperation with Russian filmmakers. Our task is to provide maximum support to Ukraine." But the question arises again – support how exactly?

Baumann stressed that cooperation with Russia has become impossible since the events of 2014, and the current situation "is absolutely unacceptable." "Today there is no point to talk about Russia or cooperation with Russian filmmakers. Our task is to provide maximum support to Ukraine." But the question arises again – support how exactly?

"As part of a minority co-production with Germany, we gave marketing budget to one Ukrainian project – Pamfir. But with production it is more complicated because we don't have a special Ukrainian law at the moment that would give advantage to Ukrainian projects and change the regulations, – she says. – It will not be a problem if a German producer applies with a Ukrainian director. But still, there has to be a certain number of German talent attached, and you have to spend the money in Germany – you cannot take it somewhere else. The only film fund in Germany that can give money "outside" is the National Film Fund, but the film must qualify as a German project, so this scheme would not work for Ukrainian films. Certain nuances can be solved individually, but the general question is: how much German funding system can finance Ukrainian films while being Ukrainian and not German ones? And this question is not resolved."

When Ms. Baumann was asked about the World Cinema Fund by Berlinale, which this year opened the opportunity for Ukrainians to apply, she answered the following: "It’s a nice fund, but there will be one or two projects. And this does not solve the problem. It's not enough. We have to think about what else we can do. It's no secret that the situation will not change next month. The war is going to be long, and the financial problems will take way longer. So we have to look into the future and make a plan that goes a little bit further. Ukraine is a big country, it has a lot of talented people, we need to think on a bigger scale on that."

Producer Darya Bassel also mentioned the problem of "how to make Ukrainian films remain Ukrainian".

"On one side, we have huge support, from the European market and a lot of international film funds are opening their doors to Ukrainians, they are opening special programs, and grants. On the other side, when you start going into details, you notice interesting things, – she noted. – For example, right now I am about to apply with a Polish co-producer for the development financing of a script. There is a special program that was created by the Polish Film Institute for Ukrainian-Polish co-production after the war started. And the interesting thing is that as a result of this grant a script should be developed and the rights will belong to the Polish co-producer, not the Ukrainian one. That is, there are many interesting things that should be discussed on the international level."

"On one side, we have huge support, from the European market and a lot of international film funds are opening their doors to Ukrainians, they are opening special programs, and grants. On the other side, when you start going into details, you notice interesting things, – she noted. – For example, right now I am about to apply with a Polish co-producer for the development financing of a script. There is a special program that was created by the Polish Film Institute for Ukrainian-Polish co-production after the war started. And the interesting thing is that as a result of this grant a script should be developed and the rights will belong to the Polish co-producer, not the Ukrainian one. That is, there are many interesting things that should be discussed on the international level."

And until the situation changes, what is left for Ukrainian filmmakers? "Meanwhile we can do such panel discussions, to bring Ukrainian films to the festivals – to be heard as much as possible. And the great thing is that we have a lot of great films for this," Darya summed up.

There is nothing to add here.