This fall KYIV MEDIA WEEK, with the support of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), successfully held six special events in cooperation with three European industrial forums. KYIV MEDIA WEEK 2022 Travel Edition started at the Serial Killer International Festival of Web and TV Series (September 20-25, Brno, Czech Republic). The midpoint of the Forum was at the MIA | International Audiovisual Market (October 11-15, Rome, Italy). KMW 2022 completed its journey at Europe's largest content market – the 38th International Co-Production and Entertainment Content Market MIPCOM (October 17-20, Cannes, France). Being partners with KMW, MBR presents a special project – KYIV MEDIA WEEK 2022 REVIEW – a brief squeeze of the key events of this year's KMW.

You can also read this article in Ukrainian by following the link.

"The war presented us with many challenges. But it is also important to note that it gave us clarity of purpose. Something beautiful was born from this – the industry united like never before," stated Kateryna Vyshnevska, producer and Head of development and co-production at FILM.UA Group, during the panel discussion Co-production with Ukraine. How To, which took place within the special KYIV MEDIA WEEK 2022 session at the International Festival of Web and TV Series Serial Killer in Brno.

These words about unity against the background of common challenges and new opportunities that open up despite everything set the tone for the entire discussion, which was also attended by Dmytro Troitsky, the director of television at Starlight Media, Jan Maxa, the director of program development and new media of Czech Television, and Erik Roose, the chairman of the board of Estonian Public Broadcasting. David Ciaramella, communications manager at the international media consulting company K7 Media, moderated the discussion.

The purpose of the panel was to introduce the international audience (primarily Eastern European producers) to the key facts and figures about the Ukrainian industry before and during the full-scale war. And also tell about co-production projects in development and services currently available in Ukraine. How and when can Eastern European countries cooperate with Ukraine in content production? What are the current risks, challenges, and opportunities? What can be the "common denominator" for co-production projects? This and much more – in our review of the discussion.

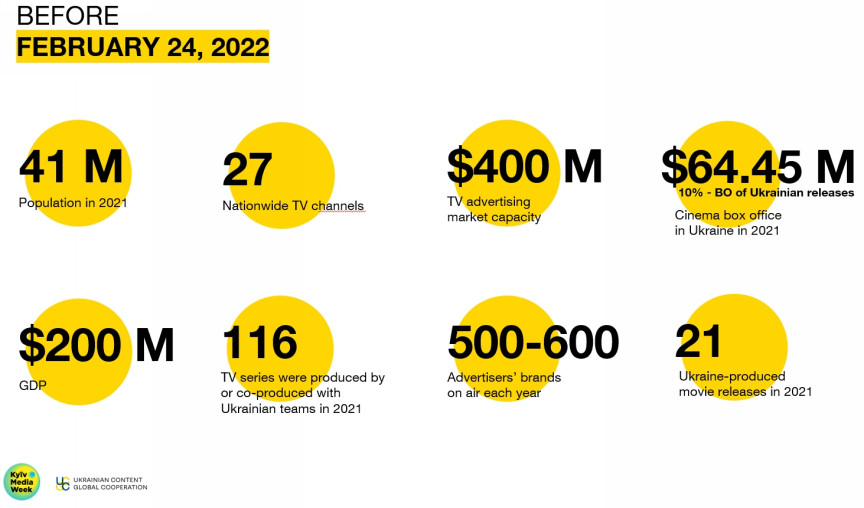

Dmytro Troitsky was the first to speak. He introduced the audience to the key figures of the Ukrainian content industry before the start of the full-scale war. He described the state of the national market before February 24, its strengths, and its players. He also recalled the successes of Ukrainian content: local originals that have worldwide distribution (most of them are produced by FILM.UA Group) and various adaptations of global formats.

Commenting on this slide, Dmytro additionally emphasized the presence of five more digital platforms in Ukraine (on July 22, the OLL.TV service, which was part of Media Group Ukraine, stopped working as well as the entire media holding)

Troitsky paid special attention to the work of Ukrainian television. He emphasized that despite the enemy's efforts (in particular, shelling of TV towers), Ukrainian broadcasters have not stopped working for a moment since the beginning of the full-scale invasion. Having joined forces, the largest television groups launched the unique format of the nationwide telethon "United News" – news content jointly produced by five newsrooms. They've been broadcasting 24/7 since February 26. The top manager also highlighted the work of the promotion and marketing teams, which refocused on the production of social videos for TV channels and the web to support Ukrainian society, and the army and counter russian propaganda. During the full-scale war, more than 450 social videos were created by the combined resources of the marathon's marketing teams.

When there were warnings of possible russian aggression, Troitsky consulted with his Israeli colleagues about their wartime programming experience: "I remember how surprised they were: 'Are you serious? Will there be a war? Well, we did news marathons’, so we had a certain recipe for how to act."

The director of television at Starlight Media said that as early as April, the channels started to produce other content besides news. According to him, such content was created mainly on iPhones via Zoom, and the programs were aimed at supporting the morale of viewers, giving practical advice, etc. Troitsky noted that this experience was unique – television was supposed to tell people how to behave in situations no one was prepared for. That is why difficult, sensitive questions appeared among the topics – for example, advice on how to act when russian soldiers break into an apartment or how to keep in touch with loved ones in conditions of constant shelling.

Of course, the issue of advertising, which is currently the most painful for Ukrainian television, was not left out. The TV advertising market froze with the beginning of the full-scale war (in particular, because advertising was completely removed from news broadcasts). But, according to Troitsky, in April, the sales teams started working on restoring the advertising market, explaining the true meaning of commercial messages at this time – both for the television economy and for society. "We are grateful to the advertisers who supported the country and the industry and returned to the air. In September, we were able to launch a new season. Of course, most of the premieres were produced before the war. But there are also several projects produced in the summer."

Troitsky noted that the Ukrainian Content. Global Cooperation initiative, launched by leading Ukrainian media groups and production companies, has become extremely important in the context of industry support.

Then the discussion moved to co-production with Ukraine and revealed several interesting aspects formed during the last months. "Co-production with Ukraine is a need not only for Ukraine," David Ciaramella emphasized one of these aspects – “After all, Ukraine currently has a unique experience. And this experience can be interesting for creators and showrunners everywhere."

According to the speakers, the war paradoxically helped to bypass one of the main stumbling blocks that made successful co-production difficult – the lack of common themes and narratives. Troitsky noted that the pain of war has become a common denominator not only for Ukrainians but also for the world, which supports us. In addition, due to the forced stay abroad in search of safety, Ukrainians became more visible in other countries and more interesting from the point of view of their values and culture.

In turn, the priorities of Ukrainians have also changed. "A few years ago, we all had the same reservations about co-production: the audience, especially of large channels, wanted a local language, local actors, etc. Ukrainians wanted to see Ukrainians. But recently, a lot has changed, mainly because of the war. After all, now Estonians, Poles, Lithuanians, and representatives of other countries are people who helped us a lot. And this creates a new interest and admiration for each other," said Kateryna Vyshnevska.

David Ciaramella presented revealing statistics: for example, 5% of the total population of Estonia currently consists of Ukrainians who left because of the war, and in Poland and the Czech Republic, this figure reaches over 10%. Which accordingly affects the content policy of these countries. "Given a large number of Ukrainian refugees in the states neighboring Ukraine, we create projects for them," commented Jan Maxa. In particular, he said that many TV programs that used to teach English and German to Czech children have now reoriented themselves to teach Ukrainian children Czech. This way, they help them adapt to Czech kindergartens and schools.

Another influential ethnocultural aspect, important for post-Soviet countries in the context of russia's aggressive policy, was touched upon by Erik Roose. He said that 25% of the Estonian population is russian-speaking, and a russian-language TV channel started broadcasting there six and a half years ago. According to Roose, the reasons why it was launched were political: for the sake of adequate communication with the Russian-speaking population of Estonia after russia seized Ukrainian territories in 2014. "We have to be very careful because a third of the russian-speaking population of Estonia is very pro-putin, they have russian passports. I am telling this to describe the challenge that we are dealing with. We have to address different communities at the same time in a dignified way," he said. Erik explained that on February 25, 2022, Estonian Public Broadcasting received additional funding from the country's government to produce Russian-language content to bring the truth about events in Ukraine. "It was the fastest political decision in Europe – it took just one day. No one asked for compensation. We initiated special streams from Ukrainian TV on our VoD platform – slots of Suspilne in English and the Ukrainian-language version of ICTV. It was a complex for providing information to the audience: it took four days to organize."

Returning to the topic of co-production, Erik Roose mentioned a FILM.UA co-production project – a mini-series A Girl From Tallinn. Development of the project started before the full-scale invasion.

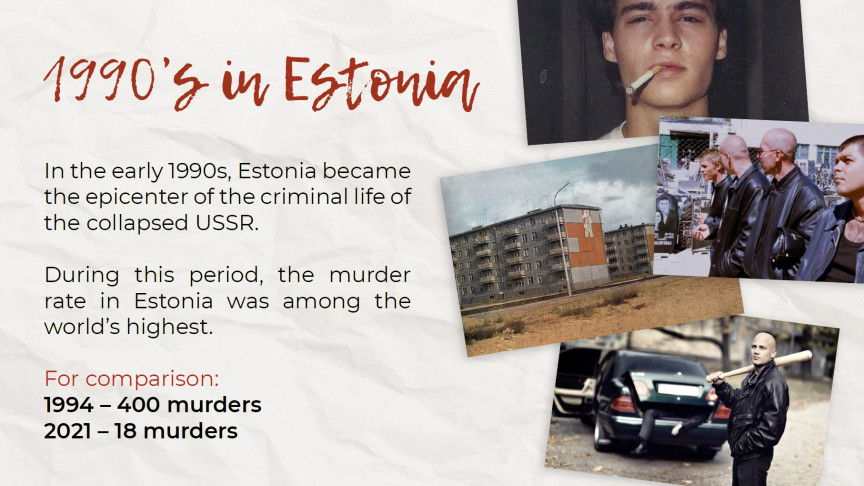

Kateryna Vyshnevska described the transformations the project underwent due to the war: "This is a classic co-production project: the events unfold in two countries. While thinking about how to do it, we decided to shoot a lot in Ukraine. We would build the scenery there, and arrange the studio pavilions. While natural locations (like the atmosphere of old Tallinn) would be filmed in Estonia. But now we have to rethink our production strategy. Of course, we are discussing the prospects of filming more in Estonia, but we are also considering other options. After all, the setting of the late Union and the 1990s is not only Ukraine and Estonia: it can be found in any Eastern European country, so other countries of the region can also join us in this project."

Vyshnevska also mentioned another FILM.UA co-production project in development open to scaling – Those Who Remain, an anthology series financed by the Red Arrow company. "Since we are talking about the anthology, these are different stories, characters, creators, and filmmakers. And it also gives us space to explore new opportunities, – emphasized Kateryna. – These are stories about those who stayed, but what about the stories of those who left? Some went to the Czech Republic, some to Poland, some to Estonia, etc. These people live among you now, and we can tell their stories together."

Reflecting on the possible pitfalls of co-production projects, Jan Maxa mentioned the ten-episode detective story The Pleasure Principle (2019). It is a tripartite co-production of Poland, Ukraine, and the Czech Republic. "It was a very interesting crime series in terms of concept. According to the plot, body parts of naked girls are found in Odesa, Warsaw, and Prague, and three police officers from three countries start investigating this case. On the one hand, it was an impressive production; on the other hand, it "highlighted" the co-production difficulties. In Poland and Ukraine, the project became very successful in the context of international distribution. But it was not well received in the Czech Republic. It turned out to be too far from what the Czech audience expects from a criminal story: it is too focused on the criminal narrative, psychological, and dark aspects. But this is a lesson for us, and we continue to look for new projects with Ukrainian partners."

In his turn, Dmytro Troitsky assured that Ukraine is currently the place to look for interesting ideas. "I'll put it simply – we have many, many projects. And the only problem is choosing the right one. Today, cooperating with Ukrainians, you are dealing with people full of stories. Before all this, we, like our colleagues from other countries, felt a deficit: what story to tell; who should be the heroes? And now we have all this in hand: we just have to choose – and make the right choice."

In his turn, Dmytro Troitsky assured that Ukraine is currently the place to look for interesting ideas. "I'll put it simply – we have many, many projects. And the only problem is choosing the right one. Today, cooperating with Ukrainians, you are dealing with people full of stories. Before all this, we, like our colleagues from other countries, felt a deficit: what story to tell; who should be the heroes? And now we have all this in hand: we just have to choose – and make the right choice."

Jan Maxa's experience testifies to how dynamic, large-scale, and local-to-global stories from Ukraine currently are. He said that even before the full-scale invasion, he started making a documentary about young Kyiv circus artists. At the beginning of the war, the entire film crew was involved in the evacuation of these children abroad. "At the same time, the narrative expanded," Jan noted – "Some of the children and their coaches are currently in Budapest, and some remain in Kyiv. The whole story has become much more voluminous, deeper, and more insightful. This is a story that arouses great international interest in many countries."

Erik Roose summarized the KMW panel discussion: "We live in an amazing time. The world is now fundamentally changing: for the first time in the last seventy years. For storytellers, this is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. Yes, we need ordinary everyday stories to distract and entertain ourselves. However, stories about how the world is changing, especially in Europe, need to be told. And we must hurry because very soon, we will have another big story – the collapse of the russian federation. I'm sure of it!"